2000. Counter-invoice

And once again, a new beginning.

A good initial idea often becomes even better the second time around through experience-based refinement. To develop the first truly usable sketches of a design that meet the higher standards that have grown over the years... sinfonìa visìbile in re minore regeneratione Bruckner In order to create a work that would posthumously stand up to the strict judgment of Prof. Dr. Anton Bruckner, I was looking for a musician who could play the symphony correctly (very slowly...) – like Maestro Karajan once did – and who could also create individual music theory scores for the Bruckner dialogues.

It's important to know that Richard Wagner, with his symphonic "music dramas," significantly inspired Bruckner, particularly in the composition of his Ninth Symphony. The challenge, therefore, was to correctly interpret the operatic musical and visual effects Bruckner envisioned in the Ninth, to coordinate them as precisely as possible, and thus to achieve an appropriate fusion of musical and scenic dramaturgy for my audiovisual symphonic poem.

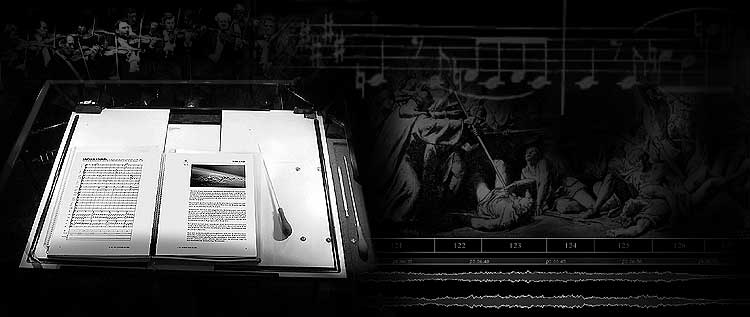

Objective: A libretto score of Bruckner's Ninth Symphony.

In this context, I noticed that entire passages of the symphony, even in recordings by well-known orchestras and renowned conductors, were consistently played far too fast (practically "botched") and thus completely disregarded Bruckner's instructions, who wrote in the score: "Please play very, very slowly!" As a result, neither the subtleties of individual passages nor any connection to visual synonyms were discernible. Therefore, it didn't particularly surprise me that apparently no one had yet discovered this audio-visual link in Bruckner's Ninth Symphony.

Lacking a suitable orchestra of my own, after reviewing various recordings of the Ninth Symphony, I used the analog recording of Bruckner's Symphony No. 9 by Karajan and the Berlin Philharmonic from 1976 and first "stretched" it in the recording studio using digital techniques to bring out these musical ideas (e.g., overtones) of the composer, which are important for visualization but had previously been neglected. Furthermore, I could now hear the dialogues much more clearly (one instrumental group calls out – another answers) and thus better assign them to synonymous symbolic scenes.

Digital film technology allowed me to access each of the 25 individual frames of a second (1/25 sec., 48 Hz in elaborately produced feature films and 3D cinemas) in a controlled manner, giving me absolute synchronization control over image and sound. This enabled me to imbue every change in tempo, every musical expression such as melody, harmony, and rhythm with a shared semiotic meaning. It's important to consider that a single film frame only acquires its true meaning within the context of the selection and composition of the subsequent frame. Similarly, only the sequence of three notes creates a universally understandable melody. Thus, the narrative facet of the symphony, the melody, or the so-called Bruckner rhythm (the combination of duple and triplet) becomes a controllable temporal signature and a measurable unit for subsequent film editing.

Through this digital trick and the completely new image and music dramaturgy created as a result, I was able to begin the visualization of BRUCKNER'S NINTH in such a way that the work is counterfactualized almost exactly as Bruckner probably imagined this adaptation as a logical (audiovisual) further development of the classical symphony.

The fact that I also re-instrumented it in a contemporary style and, for example, used an electric guitar instead of the solo flute, was something I could only have discussed with a Bruckner who was alive today.